A race requires a sense of urgency that is sorely missing from any of the world’s space programs. NASA’s 16-year target for a lunar landing in 2020 is twice the time we needed to do the job back in the 1960s. It sounds like any new “race” will be more like a trot, or even a saunter. And it would have three players, since the Chinese announced their lunar landing ambitions for the same time frame.

Both the Russians and the Chinese take a longer view of history than we do in America. I sometimes think we set our long-term milestones so far away in order to avoid the funding responsibility, and to give others the opportunity to cancel the programs. While they will have other problems, the Russians and the Chinese are more likely to meet their goals for 2020 than our own politics-plagued budgeting process allows us.

In spite of the many setbacks they have suffered in their space program over the years, and with a much smaller economy, the Russians have an unquestioned commitment to space. The Chinese also look at things on a longer-term historical scale. America’s occasional setbacks always seem to trigger agonizing reappraisals and fresh debate over whether we should even send humans into space.

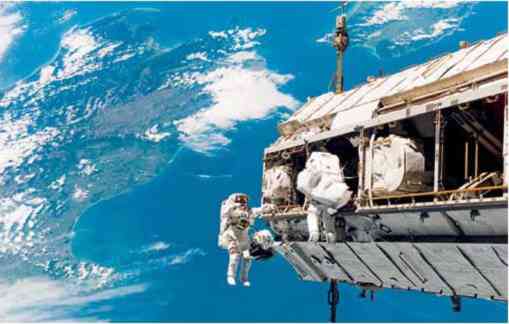

In spite of the many setbacks they have suffered in their space program over the years, and with a much smaller economy, the Russians have an unquestioned commitment to space. The Chinese also look at things on a longer-term historical scale. America’s occasional setbacks always seem to trigger agonizing reappraisals and fresh debate over whether we should even send humans into space.Between now and 2015, Roskosmos would concentrate on near-Earth space, and “complete construction of the Russian segment” of the International Space Station — no mention of the “non-Russian modules.” Someone should explain to the Russians that the ISS is a partnership, not a condominium. Partners have an undivided interest in the whole, not individual modules housed in a main vehicle.

Since first hearing that the Shuttle would be grounded in 2010, I have expected NASA to eventually turn operations of the ISS over to the Russians.

The Russians expect to propose an extension of the service life of the ISS from 2015 to 2020. That should not be too much of a problem. The problem is finding a vehicle, or vehicles, that would be capable of performing the logistics support currently accomplished by the Shuttle Orbiter. That means the ISS will be dependent on either an untested European vehicle now under development, a new Russian craft yet to be developed, or a private launch vehicle to come out of NASA’s Commercial Orbital Transportation System program. None of these will be able to match the job currently performed by the Shuttle.

Roskosmos has a preference for the reliable systems that they have been using for so long in manned flights. Perminov is planning one more major upgrade to the Soyuz vehicle that has undergone regular upgrades since the 1960s. A mission to Mars will require a totally new spacecraft and launch system. He plans to develop a new manned, reusable spacecraft by 2015, sounding a death knell for the winged Kliper spacecraft that Roskosmos has been touting for the last several years.

Roskosmos has a preference for the reliable systems that they have been using for so long in manned flights. Perminov is planning one more major upgrade to the Soyuz vehicle that has undergone regular upgrades since the 1960s. A mission to Mars will require a totally new spacecraft and launch system. He plans to develop a new manned, reusable spacecraft by 2015, sounding a death knell for the winged Kliper spacecraft that Roskosmos has been touting for the last several years. The Russians desperately need a large booster if they are to have any chance of a Moon landing. Their first big booster—the N1—was a total failure. And their last, the Energia, saw little use. The new vehicle would have to be on the scale of the Saturn V or the N1 just to mount a Moon mission. A mission to Mars would require a cluster of them.

The new launch vehicle will need a new launch pad in Baikonur—or possibly a new cosmodrome in Russia. Perminov has talked about developing such a cosmodrome for manned launches on Russian soil, even though they have a 50-year lease on the world’s largest cosmodrome at Baikonur, in Kazakhstan.

The Russians hope to have a new generation manned space platform in orbit following the demise of the ISS in 2020. They would like to use the new platform to assemble spacecraft in near-earth orbit, from where they could then depart for the Moon or Mars. Such a plan only makes sense if the platform’s orbit is at a relatively low angle of inclination, close to the plane of the ecliptic. Baikonur and other locations in Russia are too far north to be desirable launch sites for low inclination orbits. It is the same constraint that forced us to move the ISS orbit to 51.6 degrees when we invited Russia to become a partner.

A polar-orbiting platform, as some have suggested the new Russian station will be, would rule out using it as a departure point for the Moon or other bodies in the Solar System.

Perminov gave lip service to expanding international cooperation (translation, selling services) between Russia and their customers, but he went out of his way to emphasize that the new Russian station was being treated as a “Russian project” that might (or might not) evolve into an international project. He stated that, while the European Space Agency could be involved in the future spacecraft project, it too is a “Russian project and will go forward with or without their involvement.”

Russians are taking pains not to be dependent on other countries for their destiny in space, while we continue to emphasize international participation and involvement in our programs. I agree with the Russians on the need for independence. The ISS is our biggest space investment and we have rendered ourselves dependent on the Russians for its operation. We depend on them for a number of critical station systems, some re-supply and even crew transfer in many cases. This dependency will become even more critical after 2010.

Clearly, the Russian “vision for space” and timeline is about as ambitious as our own—not very. They have excellent space technology and scientists, but we have a big advantage as we saunter toward the Moon. We can follow the roadmap we developed forty years ago, while the Russians are starting from scratch.

It may make sense to encourage a modern day race to Mars, because it is a totally new milestone in mankind’s universal quest to go a little further. But America has nothing to gain in re-running a race to the Moon. Been there, done that!